A critical analysis of the TRC report presents a challenge to mainstream indigenous beliefs about residential schools

The week following the 2015 release of the summary final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on Aboriginal residential schools saw no fewer than six newspaper reports, editorials, and letters by academics and educators in Winnipeg. Additionally, a strident petition on the University of Manitoba’s website rebuked me for daring to question any of its findings.

I was vilified as promoting “colonial nostalgia,” using “racial platitudes,” being “offensively ill-informed,” peddling “bad history,” being “insensitive and insulting,” “indifferent” and “hostile” to indigenous peoples, and acting as a willing “catalyst for racist [Internet] commentary.”

Such vilification of anyone challenging mainstream indigenous views continues to this day.

In one commentary, University of Manitoba historian Adele Perry claimed that her academic discipline, history, “is a tricky business and often a harrowing one.” Still, she and her acolytes wanted all Canadians to uncritically accept the 388-page Truth and Reconciliation summary report as a kind of sacred text, each holy word the revealed, immutable and unchallengeable “Truth” about aboriginal residential schools.

My secular critique of the report in no way denies the obvious harm these schools did to many indigenous people, especially during the early decades of the program. Nor does it deny that Aboriginal ways of judging truth, interpreting evidence and seeking justice often differ widely from Western ways. What it does say is that genuine cross-cultural and national reconciliation must be based on a truth that is equally known, recognized, understood and shared by all parties concerned.

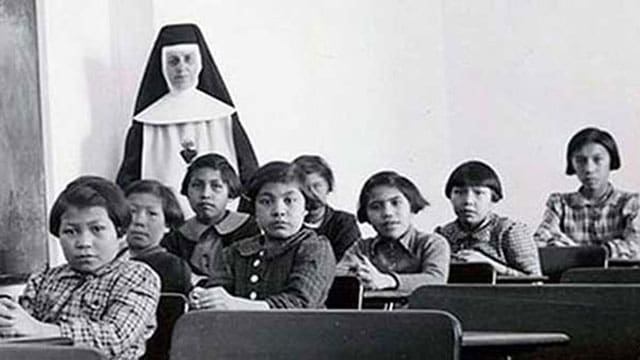

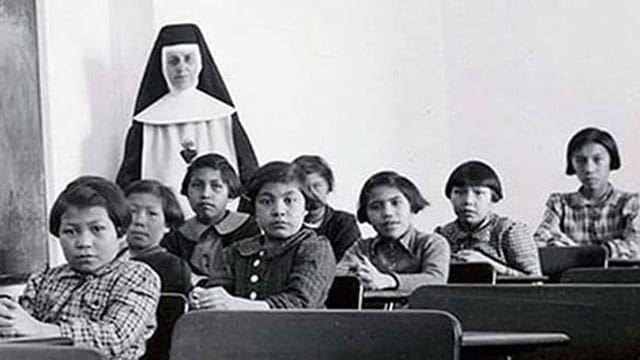

The mandate of the TRC was to “reveal to Canadians the complex truth about the history and the ongoing legacy of the church-run residential schools, in a manner that fully documents the individual and collective harms perpetuated against Aboriginal peoples.”

By indigenous cultural standards of evidence-gathering and truth-telling, perhaps it did.

However, by contemporary Western juridical and objective social science standards, the report is badly flawed, notably in its indifference to robust evidence gathering, comparative or contextual data, and cause-effect relationships. The result is that it tells a skewed and partial story of what occurred at the residential schools and how this affected its students.

Among the report’s many shortcomings are:

- Implying without evidence that most of the children who attended the schools were grievously damaged by the experience.

- Asserting as self-evident that the legacy of the residential schools consists of a host of negative post-traumatic consequences transmitted like some genetic disorder from one generation to the next.

- Conflating so-called “Survivors” (always capitalized and always applied to every former student) with the 70 percent of Aboriginals who never attended these schools, thereby exaggerating the cumulative harm they caused.

- Ignoring the residential school studies done by generations of competent and compassionate anthropologists.

- Arguing that “cultural genocide” was fostered by these schools while claiming that aboriginal cultures are alive and well

- Refusing to cast a wide net to capture the school experience of a random sample of attendees despite a $60 million budget, which would have allowed the commission to do so

- Accepting at face value the stories of a self-selected group of nearly 7,000 former students – who appeared before the commission without cross-examination, corroboration or substantiation – as representing the overall school experience.

The report also disingenuously implies that, unlike all other people on Earth, aboriginal Canadians never fabricate, exaggerate or accept money for testifying at formal hearings, as occurred under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which has already awarded $4.6 billion to tens of thousands of self-proclaimed “Survivors.”

In its eagerness to portray the native residential schools in the worst possible light and present Aboriginals as weak and helpless victims of fate, perhaps the most egregious shortcoming of the report is the way it defames the tens of thousands of strong, independent and resilient aboriginal Canadians who would look at its findings and never see themselves.

From an aboriginal story-telling perspective, the report is truly heartbreaking; from a traditional dispassionate social science perspective, it is bad research. This discordance is called a clash of paradigms, which, if not bridged, will never lead to reconciliation.

Professor Perry ended her piece by observing that “This history isn’t over.”

Neither is the need for a truthful and accurate representation and interpretation of this history.

Hymie Rubenstein, a retired professor of anthropology at the University of Manitoba, is editor of REAL Indigenous Report and REAL Israel & Palestine Report. Professor Rubenstein is co-author of Residential School Recrimination, Repentance, and Reality, an upcoming report from the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.